Community & Events

"Bailey stuffed the bills into a black camera case slung over his shoulder. He bolted outside onto Gerrard Street, jumped into a getaway car idling around the corner and fled the scene".

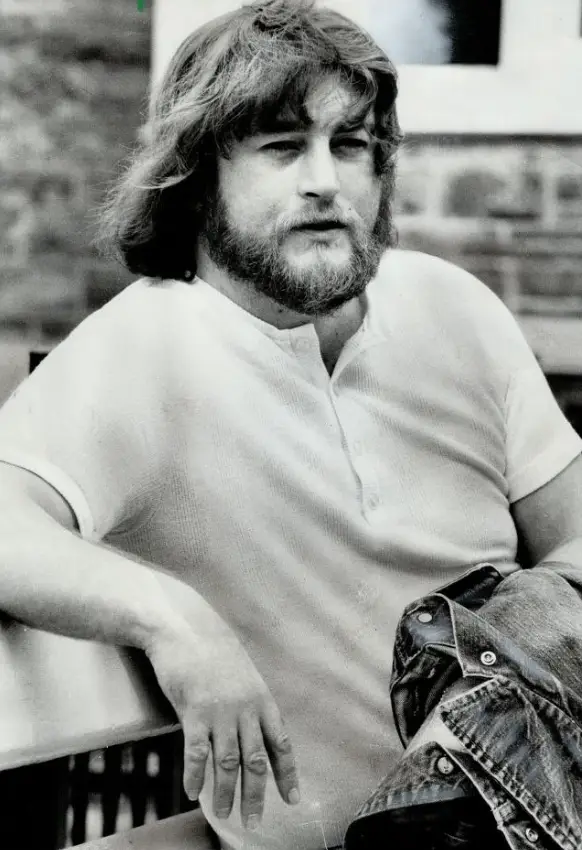

Don Bailey thrust a note into the teller’s face. “This is a holdup. Give me all the cash.” The teller sized up the mop-haired 24-year-old, stifled a laugh and replied, “This is a joke, right?” Bailey doesn’t react. Instead, he motioned toward his pocket as though reaching for a weapon. A bluff. He was unarmed. The teller wouldn’t have known this. Her face frozen in fear, she sprang open the till and scooped up a handful of bills, $1,625 to be exact. She shoved the money at him and stepped back from the counter to indicate she was finished. Bailey stuffed the bills into a black camera case slung over his shoulder. He bolted outside onto Gerrard Street, jumped into a getaway car idling around the corner and fled the scene.

An off-duty police constable witnessed the car speeding away and jotted down the plate number out of habit. Police were in pursuit minutes after the stickup, forcing the duo to ditch the car and flee on foot, but they didn’t get far. After a warning shot, Bailey was captured at gunpoint and held on robbery charges. The bank recovered all its money. Bailey’s accomplice got a three-year sentence.

A few months later, in late December, Don Bailey stood in the docket at County Court, Old City Hall, before Judge Ian MacDonnell, thirty-three years on the bench. Bailey’s lawyer pleaded that his client cracked under the strain of financial troubles. “He’s a family man, your honour.” Judge MacDonnell was unmoved and sent Bailey up for eight years. The judge shuffled papers and glared down at Bailey over the rim of his reading glasses. “If you had been armed, it would’ve been ten,” MacDonnell said before bringing the gavel down. Christmas was three days away. Bailey left a wife and two daughters on the outside to fend for themselves.

"Her sons ended up in foster care. Theodore’s struggles led him to end his life at seven. Donald, left alone, spiralled into the old pattern of foster homes and training schools."

Donald Gilbert Bailey was born in Toronto in 1942. His brother, Theodore, was two years older. Homelife for the boys was terrible. After Donald’s birth, their father, a truck driver, enlisted in the Queen’s Own Rifles, went overseas to the front and promptly disappeared. Declared missing in action at the war’s end in 1945, he was assumed dead. Donald’s mother couldn’t cope. Left to raise two boys alone, she sobbed herself to sleep every night with a bottle. Her sons ended up in foster care. Theodore’s struggles led him to end his life at seven. Donald, left alone, spiralled into the old pattern of foster homes and training schools. The reformatory. A petty thief at thirteen, he stole and lied.

"Lonely and missing family, he stared at the empty bag and asked himself, ‘Is there more to life than just this?"

On Christmas Day in 1959, police found 17-year-old Don Bailey asleep in a stolen car and arrested him for auto theft. Around this time, he married a young woman named Stella. The reckless couple lived in a plain, east end Toronto house. Both had demons to confront, but at least this was something. Don became a dad. To pay the rent, he took jobs he hated, as a milkman, a camera store employee, and a photographer. Nothing worked out. A workaday life just wasn’t for him.

The Bailey household was in turmoil. Don and Stella’s marriage, nourished by alcohol, starved of oxygen and wilted. Emotional upheaval and financial disarray equal insufficient funds and final notices, and the bank called again today. It’s all too much. And then he becomes a dad for a second time. Don cracked. The holdup was the final straw.

After sentencing, his home became an 8 by 10 foot cell in Kingston Penitentiary. Inmates call him Beetle. On the smallish side, about an inch over five feet, fortunately for prisoner #3274, bank robbers had street cred in KP. At Christmas in Kingston Pen, the Salvation Army gifted inmates with an orange placed inside a brown paper bag and a handwritten note, reading, “We’re praying for you.” Don peeled the orange, crumpled the note and sighed. Lonely and missing family, he stared at the empty bag and asked himself, “Is there more to life than just this?”

“At night, Don stood at the end of his cot and looked up at the stars, contemplating life after his release.”

Don’s conversion began after he was transferred to the new medium-security federal prison, Warkworth Institute, 40 miles southeast of Peterborough. Opened in 1967, Warkworth wasn’t your typical prison. Planners replaced cellblock tiers with an open-campus design. There were no bars on the cell windows. Secure, 14-foot barbed wire-topped fencing replaced traditional solid perimeter walls, and as a result, Warkworth inmates had a clear view of the world beyond the prison.

At night, Don stood at the end of his cot and looked up at the stars, contemplating life after his release. He began writing short stories and poems, some of which found a publisher. Warkworth’s young warden took a nonconforming approach to incarceration. Inmates wearing olive-green work pants and dark duffle coats moved around unescorted. The warden sought input from prisoners on administrative decisions that affected their lives. The dining rooms had blue and white checkered tablecloths. Academic programs were available. Industrial training was provided. Inmates could earn university diplomas through correspondence courses.

"Bailey stuffed the bills into a black camera case slung over his shoulder. He bolted outside onto Gerrard Street, jumped into a getaway car idling around the corner and fled the scene".

Don organized sports and recreation programs. When Christmas came around again, he convinced half the prison population to participate in a pageant. Under his auspices, shop-class inmates crafted seasonal scenes from wood and painted them festively. He wrote skits for inmates to act in and persuaded others to perform musical numbers. A group of inmates in Don’s unit, including Ed Laboucane, sat around in the evenings and discussed what they’d do when they got out. Ed was raised in Spruce Lake in northern Saskatchewan. His father was Metis. His mother was a socialist. Ed and Don formed a lifelong friendship. After their release, the men discussed forming a group to assist ex-cons and their families. Don envisioned a support system that would serve as a springboard, assisting former prisoners’ transition into the community and pledged to follow up once on the outside.

Upon release in July 1969, Don settled in Toronto and immediately forgot his promise. Instead, our flawed hero focused on less demanding issues. Consumed by his newfound freedom, he had long dreamed of devouring a pastrami sandwich. He flagged down a cab, instructed the driver to head to Shopsy’s Deli on Spadina and wolfed down six. On the way home, he bought a bottle of champagne and a quart of rye. His marriage was over, and he didn’t see his daughters often. Renting a room for eight dollars a week on Sackville Street, he wrote, drank too much, looked for work and visited his parole officer, as required.

And then a letter arrived from Ed, still behind bars in Warkworth. “We haven’t forgotten you. Don’t forget us.” The brief correspondence jolted Don to action. A couple of days later, Don was sitting on a bench outside Riverdale Zoo in the afternoon, smoking a cigarette, when fate intervened. A stranger sat beside him and introduced himself. The fellow, Barry Morris, struck up a conversation. Barry told Don about his involvement with the Christian Resource Centre at 297 Carlton Street, an outreach ministry founded in 1964 by members of Rosedale United Church. In response, Don informed Barry about his concept for a community agency established to assist former inmates. Barry liked the idea and invited Don to drop by the CRC offices to check out the place and discuss his plan further.

Don’s idea of supporting former prisoners gained traction. With the assistance of volunteers from the John Howard Society, university students, and members of service clubs, Operation Springboard began to take shape. Volunteer Margaret Nistad played a crucial role in establishing a transportation program for family members visiting loved ones in federal institutions situated in and around Kingston, Ontario. After his release, Ed Laboucane and other Warkworth inmates joined the cause, further expanding the agency’s reach and impact.

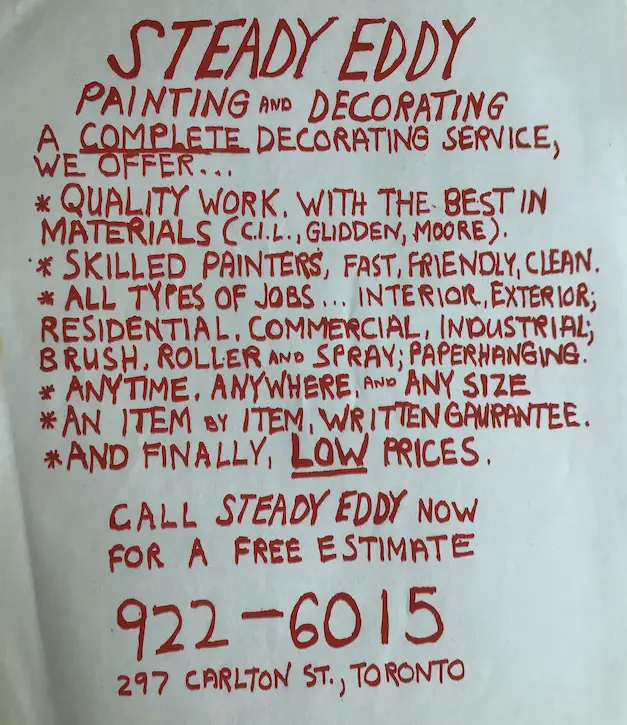

In January 1971, Don and Ed were the only staff on the payroll. Springboard’s precarious finances got a boost after lawyer, community organizer, Ward 7 alderman and future mayor John Sewell, who would eventually become a Springboard board member, secured a $5,200 Atkinson Foundation grant. Things came together faster than anticipated. The regional director of penitentiary services granted permission to the fledgling agency to provide services in prisons. They counselled wives whose husbands were serving time and provided rudimentary employment opportunities for parolees, including the flyer distribution service Flyer Force, the paint and decorating service Steady Eddy, and a moving service.

Don remained at the helm for only a short time. By June 1972, he had moved on. In the following years, Don maintained a close bond with his daughters, married twice, and expanded his family. As his creative talents flourished, he made significant contributions to society, running halfway houses and working with foster children. The social activist and author of 15 books died unexpectedly in 2003.

Don Bailey’s journey is a testament to the power of personal growth and transformation. Ultimately, our flawed hero may have robbed a bank, drunk too much and spun a few yarns, but recognizing his flaws, he accepted people on their terms. Nothing outshone his compassion for those who shared life experiences similar to his own. In the subsequent years, the agency founded by Don and others who served time has evolved into the multi-service organization we know and value today.

(Content from Don Bailey’s Memories of Margaret, My Friendship with Margaret Laurence.)